What a Tour of China's Factory Floor Reveals About the Future of Clean Energy

by Thai Nguyen, Partner at MCJ

Last October, I had the opportunity to join a group of climate tech founders and investors on a tour of companies, manufacturers, and suppliers that make up the Chinese green energy ecosystem. This tour was the fourth iteration of a trip that made headlines over the summer for the impression it left on leading Western climate tech investors. Part of the sentiment expressed by attendees of that initial trip—that China has advanced in key areas of climate tech beyond the West’s ability to catch up—struck me as a bold claim that I was intrigued to judge for myself. The trip was organized by Sharon Chen and Roger Zhang, founders of Persimmon Systems, which works with Western companies to navigate the Chinese advanced manufacturing landscape by helping source supply chain partners. Thanks to Sharon and Roger’s close relationships and connections, commonly referred to as guānxì (關係), my group had the unique opportunity to visit several leading companies and startups and meet with members of their leadership1:

Reports of China’s rapid progress in developing and deploying green and carbon-free technologies, such as solar, wind, batteries, EVs, and nuclear, have dominated news headlines recently. While the flood of cheap Chinese exports has sparked fears as well as protectionist policies in various countries, many have credited China’s cost-competitive renewables as being a boon for developing nations and the effort to curb global greenhouse emissions. At the COP30 climate conference in Brazil in November, the culmination of China’s emergence as a “renewable-energy superpower” was on full display, leading many to proclaim China had supplanted the U.S. as the world’s leader in clean energy. To help those of us outside of China make sense of what’s being reported, I’m sharing observations from my brief time on the ground. For a more in-depth summary of insights, I highly recommend reading “A tour of China’s electrostate,” written by Kim Zou, CEO and Co-Founder of Sightline Climate, who was one of my companions on the trip.

Speed, Scale, & Specialization

Few would be surprised to hear of China’s penchant for building at breathtaking speed. Whether it’s deploying solar farms larger than Manhattan, laying high-voltage transmission lines across the country, erecting massive hydroelectric power stations, or building the biggest nuclear fleet, China has shown a steadfast commitment to its domestic industrial advancement that is envied the world over. In his book Breakneck: China’s Quest to Engineer the Future, author Dan Wang asserts that this stems in part due to an ingrained engineering mentality that pervades China’s technocratic leadership and bureaucracy. Having read Wang’s book and hearing him speak in person before traveling to China, I had some expectations of what a visit might reveal. However, it was only by speaking with local insiders and glimpsing the internal workings of these companies did I truly appreciate the sheer magnitude of the country’s manufacturing output and technical sophistication.

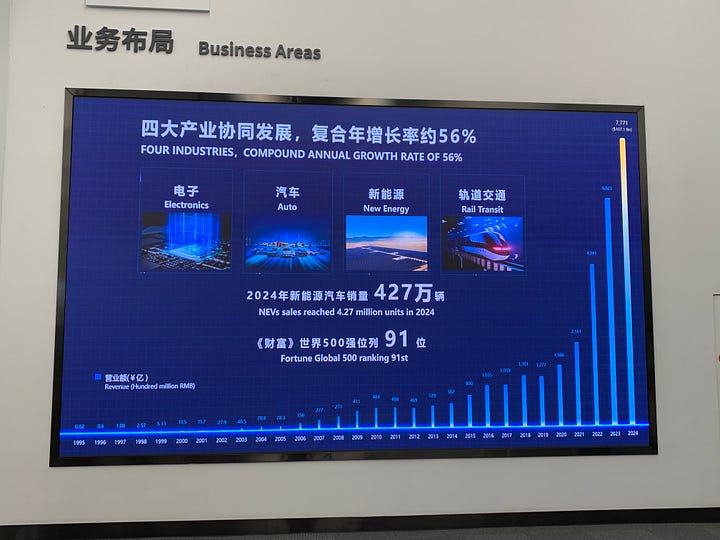

Once I landed in China and met with my group, we embarked on a visit to BYD, a leading battery producer as well as the world’s largest EV maker. Deriving its name from the acronym “Build Your Dreams,” BYD started in 1995 as a battery manufacturer, an industry in which it continues to command a leading share of the market along with its Chinese competitor CATL. At BYD’s headquarters in Shenzhen, our hosts walked us through the company’s history and evolution. I was awestruck not just by the company’s high-velocity EV sales volume, but also by its innovation. Reaching heights of 4.27 million in EV sales in 2024, BYD sold 4.6 million in 2025, securing nearly 21% of the world’s EV market.

BYD has accelerated its sales growth over the last several years and, in 2025, dethroned Tesla as the largest EV brand by sales volume. There are several confluent factors worth noting that have propelled BYD and its Chinese peers to market dominance.

Owning the upstream supply chain

Controlling the upstream supply chain endows a durable advantage to many Chinese companies, enabling them to expand downstream and compete both on cost as well as quality. As an example, BYD has leveraged its specialization as a battery manufacturer to produce EVs, energy storage systems, and electrified rail that, in many cases, are more advanced and cheaper than those of its domestic and foreign competitors. Unveiled this year, BYD’s 5-minute fast charging battery is one such manifestation of the company’s competitive edge. With the BYD Super e-Platform, EV owners can enjoy megawatt charging, getting 400 kilometers (250 miles) of range in nearly the time it takes to fill up the tank at a gas station. Ostensibly, BYD and other Chinese EV OEMs have not just narrowed the gap between their Western competitors but, in many ways, have leapfrogged them in terms of innovation and quality—a new reality that Ford’s CEO, Jim Farley, has echoed. In Breakneck, Wang credits the foresight of the Chinese government in paving the way for Tesla’s entry into the Chinese automotive market. He notes that Tesla had the effect of catalyzing consumer interest in EVs as well as forcing Chinese OEMs, like BYD, to compete at a higher bar. This phenomenon, dubbed the “catfish effect,” was akin to introducing a larger fish into a pond, forcing the others to swim faster.

Beyond Industrial Policy

The role of China’s central government and its years of commitment to its green energy industrial policy cannot be overstated. For decades, the central government has prioritized key sectors and areas of innovation it deems as strategic and representing industries of the future. Since 2009, it has reportedly invested nearly a quarter of a trillion dollars into the EV space alone, which has taken the form of subsidies enabling Chinese EV companies to achieve scale. I learned that China’s industrial policy is defined at the top by the central government, but implemented locally by provincial officials. In contrast to the elected politicians in the West, Chinese provincial leaders are appointed by the central government and primarily judged on their ability to drive GDP growth and economic development. This political structure incentivizes local leaders to attract businesses, provide support, and eliminate red tape, an issue many founders in the U.S. have decried as hobbling the speed of development. One American climate tech founder I met on the trip, who was visiting China to explore setting up a factory, shared his story of meeting with a local official:

“Meeting with Chinese local governments was so eye opening. They literally have KPIs - one govt needs to bring 10 new cos with 100M RMB investment per year. Our first meeting they brought a rep from every department we would interact with. Financial incentives (free money) actually have mainly turned off due to recent belt-tightening (or at least that’s what we were told), but philosophically 100% alignment. Dinner with one mayor and he literally called one of our potential customers during our dinner and was trying to sell [...] for us! We told him we are planning to break ground mid next year, his response was ‘if I get you a customer now can you break ground by December? You need to go faster’ 🤯”

When I asked the founder how this compared to engaging with officials in America, he replied, “We haven’t had anywhere near such an enthusiastic reception anywhere in the US that we’ve looked so far.”

Manufacturing Speed and Specialization

Our visit to the headquarters of CATL in Ningde, Fujian province was similarly eye-opening. The largest battery maker globally with a 38% share of the EV battery market, CATL is a supplier of batteries to EV OEMs as well as energy storage and battery management systems. Like BYD, CATL owns the battery-making supply chain from the production of the fuel cells to the assembly of the battery packs. Its sprawling headquarters includes a large manufacturing facility in which we were given a rare tour of the factory line.

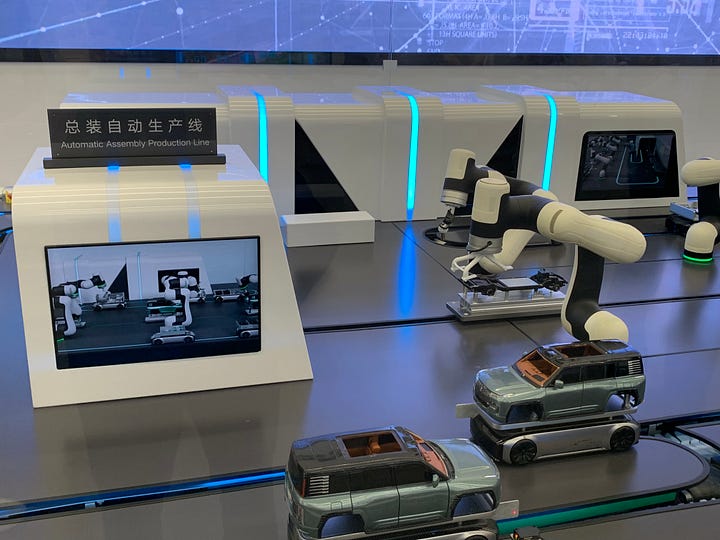

As we traveled through a long labyrinth of corridors, we peered through glass windows and observed the lengthy process of how battery cells, namely the electrodes (anode and cathode), are made starting from raw minerals. On the production line, a slurry of lithium and other chemicals are processed into long strips of foil, rolled and stacked with delicate precision, and ultimately assembled into a battery cell. What was most impressive about witnessing the electrode manufacturing process—which accounts for 40% of lithium-ion cell capital expenditure—was not just how intricate and precise it was, but also the level of automation involved. While there were people to monitor and provide quality assurance, the production line was heavily automated, leveraging complex machinery and robotics. I had heard of China’s so-called “dark factories,” which are supposedly so fully autonomous that the absence of humans negates the need for indoor lighting, and CATL’s advanced manufacturing seems to come close to that. The speed with which new production lines—be they for batteries or solar panels—could be purportedly stood up was impressive. We often heard the time to assemble meaningful manufacturing capacity in China is measured in months, whereas in the West it may require years.

The Crucible of Chinese Competition

It’s worth commenting on the immense size of the Chinese market, as well as the Hunger Games-style competition that produces its industry victors. As an example, the Chinese EV market is so large that it eclipses all vehicle sales in the U.S.; and the immense competition across a vast landscape of OEM brands means that companies that are able to survive in China are the ones best positioned to expand abroad.

Involution and other headwinds

While China has made headlines for its ability to dominate industries, many sectors, like EVs and solar panels to name a few, are gripped in fierce domestic competition as a result of an economic phenomenon that has come to be known as “involution (nèijuǎn 內卷).” Partly a consequence of China’s industrial policy, involution is where companies, beset with an excess of supply and a dearth of domestic demand, compete on price in a “race to the bottom.” In some ways, many Chinese industries are victims of their own success, achieving such vast scale that there’s a glut of capacity. The result has been scores of unprofitable companies that are making little to no margin on the products they sell. An intensifying challenge across sectors, involution was top of mind among many of the business leaders and founders we spoke with, seemingly much more so than U.S. trade tariffs which seldom was expressed as a major concern. The severity of involution has led some to predict an implosion of the Chinese EV market. For their part, company leaders we heard from felt confident they can always modify output and that, given China’s forecasted long-term growth, they will be able to fill today’s surplus capacity with tomorrow’s demand.

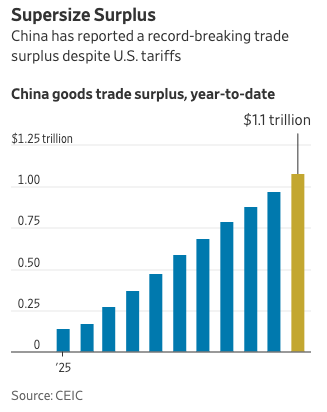

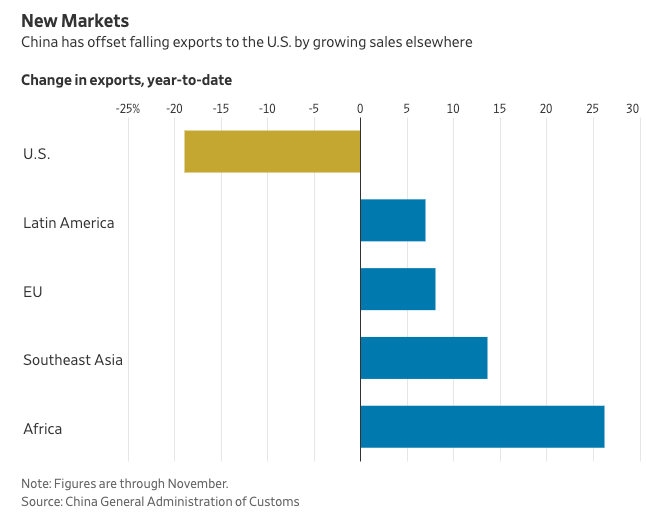

China’s economy is contending with two seeming contradictions. Overall domestic investments are stagnating in areas such as manufacturing; however, in spite of steep U.S.-imposed tariffs, China’s trade surplus has reached an all-time high. This is due in part to the country’s ability to increase its exports to markets in the EU and the Global South. Addressing anemic domestic demand while continuing to build a “fortress” of economic self-sufficiency is a priority for the Chinese leadership.

Nuances to the Great Decoupling

As U.S. trade tariffs have risen on Chinese manufactured goods, we have seen a number of MCJ portfolio companies attempt to shift away from Chinese suppliers. Representative of a greater decoupling from the Chinese supply chain that’s occurring across American industry, companies have moved to “friendshore” their supplier network to places like Vietnam or in some cases “re-shore” to the U.S. Witnessing the extent to which Chinese companies have become entrenched in key areas of the green energy supply chain, I realize there are nuances to that trend. First, there are some industries for which China is the only reliable supplier for the foreseeable future. Even accounting for heightened tariffs, China will remain, in the near term, the optimal source of manufacturing for certain sectors. Second, many of the alternative factories being established in countries like Vietnam are, in fact, run by Chinese companies.

There’s another dimension worth noting as well. While Western businesses have long had to bear the risks to their intellectual property as a part of doing business in China, I met some founders keen on identifying ways to sell into the Chinese market. It remains to be seen whether, over time, we’ll see more than just NVIDIA GPUs and soybeans as the Western goods that are imported to China in large quantities. That might be wishful thinking given China’s policy direction toward economic self-reliance.

The Return of the Sea Turtles

Apart from the impressive automated factories and fancy EVs, one of the more subtle observations I noticed is the role of expat talent, Chinese professionals returning to their homeland after being educated and trained in the West. Among the companies we visited, we met individuals who had studied or built their early careers at prestigious research institutions and corporations in America. These returning Chinese expats, sometimes referred to as “sea turtles” (hǎiguī 海歸), often had very impressive resumes, English fluency, and clearly contribute both technical as well as a unique insight to their Chinese employers. When I asked one of our organizers whether opportunities in China lured them home, I was told that, more often than not, it reflects the challenging process of obtaining an H-1B visa to remain in the U.S. Living in an American city in which Chinese foreign students abound, I feel our inability to retain such talent that we have cultivated on our soil is an unforced error that stymies our unique advantage in attracting the very best from around the world.

Navigating Risk and Opportunity

After my illuminating tour, I understand the reasons for some Western investors’ aversion to investing in companies that would be in direct competition with those in China. The advantages that many Chinese industries have developed are structural and have been honed over decades. For Western investors and entrepreneurs, China’s capacity to refine, scale, and dramatically lower the cost of a technology represents both a significant opportunity and a potential risk. This factor must be carefully considered for any technology under evaluation. In fact, some investors who have traveled to China are posing a critical question during investment committee decisions: Is the company positioned to survive Chinese competition? Nevertheless, I hold a perhaps naive hope that, in the long run, collaboration between Western and Chinese climate tech companies will ultimately prevail. The potent combination of leading Western innovation and technology with China’s unparalleled speed and capacity for deployment creates a powerful global opportunity for critical decarbonization. This synergy, already evident in sectors such as solar and batteries, allows for rapid, large-scale implementation worldwide. For those curious about the vibrant Chinese climate tech sector, I highly recommend visiting to experience its dynamism firsthand. A trip is sure to offer a revealing glimpse into the future of climate technology for decades to come.

If you’re interested in opportunities to join future tours of China’s climate tech ecosystem, you can contact Sharon Chen (sharon@persimmonsystems.com).

The companies visited during the China tour include BYD (largest global EV manufacturer); CATL (largest global battery manufacturer); GCL Solar (a manufacturer of PV solar); Nio Capital (CVC of EV brand Nio); SolidLight (a startup making battery cells for small electronics); HydoTech (a green hydrogen hardware manufacturer); GCL Perovskite (a manufacturer of perovskite solar); Tencent’s CarbonX Program (offset buyer and low-carbon technology funder); Windrose (an electrified trucking startup); and Envision Energy (a global leader in wind turbines, hydrogen energy, and BESS systems).

Inevitable Podcast

🌌 Can you really run a data center in space? Philip Johnston’s Starcloud recently launched the first orbital GPU and he explains why the economics are starting to work—from 24/7 solar power to radiative cooling to rapidly dropping launch costs. Listen to the episode here.

MCJ Portfolio Jobs

Check out the Job Openings space in the MCJ Collective Member Hub or the MCJ Job Board for more.

Life Sciences Account Executive at Artyc (Remote)

Test Data Systems Engineer and Deployment Engineer (Data Analytics) at Base Power (Austin, TX)

Executive Assistant - Legal at Crusoe (Denver, CO)

Senior Mechanical Engineer, High Volume Design at Heirloom (Brisbane, CA)

Production Technician at Lightship (Broomfield, CO)

Strategic Partnerships Lead at Mill (San Bruno, CA)

Senior Mechanical Designer and Mechanical Engineer (Infrastructure) at Pacific Fusion (Albuquerque, NM)

Supply Partnerships Manager at Patch (San Francisco, CA)

Software Engineer - ML & Platform and Manager of Policy and Market Development at Rhizome (San Francisco, CA)

Events

❄️ Progression 2026 is an invitation-only Clean Energy and Climate Resilience conference taking place April 2nd & 3rd, 2026 in Park City, Utah, in partnership with the U.S. Ski & Snowboard Team. They convene leading investors, founders, and proximity stakeholders around a curated slate of Series A - C companies actively fundraising.

Progression 2026 Attendee Registration link (Deadline 3/22/26)

Progression 2026 Startup Application Link (Deadline 2/8/26)

MCJ Newsletter is a FREE email curating news, jobs, Inevitable podcast episodes, and other noteworthy happenings in the MCJ Collective member community.

💭 If you have feedback or items you’d like to include, feel free to reach out.

🤝 If you’d like to join the MCJ Collective, apply today.